I. INTRODUCTION

The minhag of placing a headstone or marker on a grave is a significant custom. This practice begun with Yaakov Avinu himself, who built a monument for his wife Rachel, as mentioned in the book of Bereishit (35:20)1. Erecting gravestones for the deceased is considered a halachic obligation2.

There are six main reasons why we place a marker or tombstone, known as a matzeva:

- The matzeva serves as a monument, reminding relatives and others of the deceased3.

- To prevent any embarrassment to the deceased's honor from the exposed earth covering the grave4.

- To protect against impurity, as kohanim are forbidden to encounter the dead. Erecting a matzeva above the grave would alert people to its presence and help them avoid approaching it, thus maintaining ritual purity5.

- By erecting a matzeva and inscribing the person's name, their memory and good deeds are kept alive6.

- The gravestone (matzeva) serves as a marker for the grave location so to enable the custom to pray at the graves of tzadikim (righteous individuals) and relatives. This is beneficial for the soul of the deceased, and through this merit, the soul can intercede with Hashem to assist the one who prayed for them7.

- According to Kabbalah, the matzeva serves as a resting place for the nefesh, the lowest level of the soul, which remains eternally near the grave. The tombstone is thus built to honor this level of the soul and symbolically define its space8.

II. TYPE OF TOMBSTONE

A simple stone is considered an appropriate choice for a gravestone, and there is no requirement to spend a significant amount of money. Rav Ovadia Yosef cites9 the Chafetz Chaim that writes10 that “some people wish to make an eternal remembrance for the souls of their parents, and they do so by building structures of precious marble, engraved with gold lettering and decorations and carvings. They spend excessive amounts of money all in the belief that this will bring peace to the soul of the deceased. This is a big error. Once a soul has left this world, the only thing that matters to them is mitzvot and study of Torah. It would be better for them to build a less expensive structure and use the extra money to donate a set of Talmud (or other Torah books) to the synagogue in memory of their parents. So too, they could use the money to establish a free loan society (gemach) in their memory. This would be of much greater benefit to their souls… The mitzvot children perform after the passing of their parents atones for their parents’ souls.”

Having a large tombstone span over two graves is permissible. Individual headstones for each grave are not mandatory11. However, some poskim advocate for separate stones for each person based on Kabbalistic reasons12.

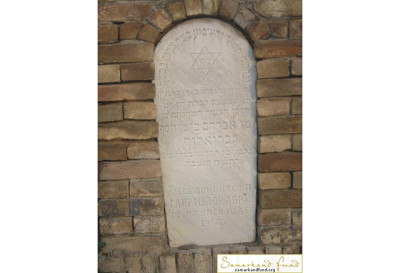

III. WHAT TO INSCRIBE ON TOMBSTONE

One should write the Hebrew name of the deceased and the Hebrew name of his father or mother on the tombstone. The custom is to write the last name as well13. One should also write the Hebrew date of the passing of the deceased. It is forbidden to write the secular date on the tombstone14. See note for more15.

It is customary to inscribe the Hebrew letters תנצב"ה. This abbreviation stands for the words תהא נשמתו ה צרורה בצרור החיים, which translate to "May his/her soul be bound in the bundle of life.” Tzeror Hachaim (the bundle of the living) is the highest level of Gan Eden, the final resting place for the soul. After completing its stay in Gan Eden, the soul enters Tzeror Hachaim, where it is privileged to witness the glory of the supernal Holy King. This level is considered higher than the realm of all the holy angels.

It is important to remember to limit the extent of praise on a tombstone, as the soul is held accountable, and excessive praise can lead to judgments and prosecution against the deceased16. To inscribe poetry on the tombstone is definitely not a Jewish custom.

IV. PICTURES ON TOMBSTONES

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef was asked17 by the chevra kadisha of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, about placing photos of the deceased on tombstones. He explained, based on the writings of our gedolei poskim, that this practice is forbidden. This prohibition is based on several factors.

- Cemetery has a status of Bet Hakneset

The Gemara in Megilah (29a) cites a beraita stating that we should refrain from acting lightheaded or frivolous within a cemetery. This prohibition stems from the respect owed to the deceased and the inherently serious nature of the place.

The Radbaz18 writes that the laws of the cemetery is similar to that of a synagogue, as prayer by the living is customary there. The Shiltei HaGibborim (Sanhedrin 15a) interprets the Rambam's view as establishing a parallel between cemeteries and synagogues regarding certain laws. This implies that the prohibition against frivolous behavior in synagogues extends to cemeteries as well. Consequently, actions like relieving oneself (even beyond four amot), engaging in calculations, grazing animals, using the cemetery as a shortcut, and eating or drinking within its grounds19 would be prohibited. Similarly, smoking in a cemetery would be considered inappropriate due to its association with frivolous or lightheaded activity20.

Following this logic, if flat images are prohibited21 in a synagogue22, they would also be prohibited in a cemetery.

Because people often visit the resting places of their loved ones to pray to Hashem and seek their intercession and pray for the deceased as well, placing pictures in a cemetery is strictly prohibited, similar to the prohibition against placing them in a synagogue. The Maharam Shick23 discussed the case of a man who placed a tombstone on his father-in-law's grave with an engraving depicting the deceased's head and upper torso. Since the laws governing cemeteries are similar to those of synagogues—as prayer occurs in both places—the rabbi ruled that it is strictly prohibited.

- Images

Beyond prohibiting the worship of idols, the Torah (Shemot 20:4) further forbids even constructing them, even with no intention of worship. Furthermore, the Torah (Shemot 20:20) prohibits the creation of objects resembling Hashem's "servants," even for decorative purposes. This includes figures representing humans, eagles, bulls, lions, the sun, moon, and astrological constellations (mazalot).

Since humans are created in the likeness of Hashem, creating an image of a person is considered akin to making an image of Hashem, and is therefore prohibited .The Rambam, (Avodah Zara 3:10), prohibits creating decorative images of the human form alone, a ruling echoed in the Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh Deah 141:4).

Based on this, Rabbi Moshe Sofer of Pressburg (1762–1839), also known as the Chatam Sofer, was asked about someone placing a prominent image of the deceased on their grave. He ruled that fashioning human images on gravestones is strictly forbidden (Likkutei Shu"t Chatam Sofer, vol. 6, Siman 4).

The Maharam Shick24 prohibits images on gravestone due to the prohibition of creation of objects resembling Hashem's “servants”. Citing his teacher, the Chatam Sofer, he applies the Talmudic term chadash asur min haTorah ("new is forbidden by the Torah") as a slogan to express his strong opposition to the practice of placing pictures on gravestones. This term, originally referring to the prohibition of eating chadash (new grain) before the Omer offering, is used here figuratively to convey the Chatam Sofer's disapproval of any new customs or practices that deviate from established Orthodox traditions.

Rabbi Malkiel Tannenbaum in Shu"t Divrei Malkiel (5:257) forbids25 painting the image of the deceased on their tombstone. He particularly cites concerns of Kabbalists who believe it is detrimental to the neshama (soul). They maintain that pictures on graves attract impure spirits, causing great sorrow to the deceased26. Rav Yonatan Eibshitz27 also warns against creating or keeping human or animal images. He says such figures embody evil spirits and bring harm.

- Gentile Practice

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef further explains that this practice resembles the gentile custom of placing pictures of loved ones on gravestones, and Jewish law prohibits following gentile customs. This view is also shared by Rabbi Shmuel HaLevi Wosner,28 who writes that one should encourage the family to remove the picture from the stone if it is already present.

V. LONGSTANDING TRADITION

Our community has historically been known for its strong adherence to established customs and traditions. For generations, our ancestors refrained from placing pictures, secular dates, or using secular language on gravestones.

This practice emerged in the Soviet Union during the 1960s, a time when religious expression was severely restricted and access to Torah scholars was limited. This historical context may have contributed to the adoption of this practice within the Jewish communities in the Soviet Union, including ours29. Our longstanding tradition should be brought back, so our loved ones can have the same tombstones as their ancestors.

Many claim that it is important for others to be able to see and identify who is buried there. However, this is an argument that lacks merit. The visitors who come to the grave to pay their respects are likely close relatives who already know where their loved one is buried, and they do not require the assistance of a picture or inscription.

VI. Respect to The Deceased

Consider this thought experiment: If a deceased relative were miraculously brought back to life for a brief moment and asked, 'Should we place an image on your grave to help people recognize you?' They, having witnessed the truth and residing in the world of truth, very well will respond, 'This is unnecessary. Please remove the picture from the gravestone.’

Many of these considerations (placing pictures, expensive stones, secular dates etc.) stem from the notion of extending respect and honor to the deceased, similar to how it's shown to the living. However, this reasoning contains a flaw. The deceased no longer require or benefit from earthly honor and respect, residing in the world of truth. Acts of honor by living relatives in this world do not affect the deceased, whose true aspiration is elevation in the higher worlds or, at the very least, maintaining their current standing. Any actions done in their name that could lead to a decline in their spiritual level should be avoided. Believing that not having an image on a tombstone diminishes the deceased's status compared to other deceased loved ones is unrealistic. Such acts primarily serve to enhance the living relatives' sense of status and respect, at the expense of the deceased's spiritual well-being.

Our approach to honoring and respecting the deceased should have one clear objective: how can we elevate their soul in the afterlife? This perspective should extend beyond the topic of gravestones and permeate all aspects of afterlife practices, including yushvo (mourning meals). When considering the purpose of the meal, the atmosphere, who participates, the amount of Torah study, and the gifts given out to guests, we should always prioritize the spiritual well-being of the deceased.

Unfortunately, if only one family member comprehends this principle while others remain focused solely on the concept of "respect," it can create conflict. Open communication and education are crucial in ensuring everyone is aligned with the ultimate goal of elevating the deceased's soul.

1 Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (Igrot Moshe Y.D., Vol. 4, Siman 57), explains that Hashem commanded Yaakov Avinu to erect a tombstone.

2 Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Avel 4:4

3 Lechem Hapanim (376)

4 Teshuvot Hageonim, Siman 94

5 Bava Batra 58a, Shu”t Harif (313)

6 Malbim (Vayishlach)

7 Sefer Tzeror Hamor (Vayishlach)

8 The Arizal in Shaar Hamitzvot (Vayechi), Chesed Leavraham (Ma’ayan 5, Nahar 32)

9 Chazon Ovadia, Avelut Vol. 1 pg. 455

10 Ahavat Chesed, Chapter 15

11 Chazon Ovadia, Avelut Vol. 1 pg. 456

12 ibid, citing Shu’t Mahari Shteiff (Siman 209)

13 Illuy Neshamot, 29:4

14 Chazon Ovadia, Avelut Vol. 1 pg. 454

15 The Maharam Shik (Shu”t Maharam Schick, Yoreh Deah 171) writes that using secular dates violates the prohibition against using avodah zarah (idolatrous practices) as a reference point, since the secular calendar is based on Christianity. Similarly, Rabbi Rachamim Palagi (Yafeh Lalev, Vol 5 Siman 178:3) considers using a secular date a violation of chukot akum (gentile customs).

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Shu”t Yabia Omer Vol.3, 9:3) emphasizes the importance of adhering to the Jewish calendar for counting months, as stressed by both the Ramban (commentary to Parshat Bo) and the Chatam Sofer. The Torah designates nissan as the "first" month, implying that it holds a unique position within the Jewish calendar. When using a secular calendar, one is not acknowledging nissan's specific designation as the first month

16 Shu”t Chaim Sha’al (71:6), Chochmat Adam (Klal 155:6)

17 Chazon Ovadia - Avelut vol. 1 pg. 455

18 Shu”t Radbaz 4:106

19 Y.D 368:1

20 Chazon Ovadia - Avelut vol. 1 pg. 435

21 See Shu”t Avkat Rokhel (siman 63) where Rav Yosef Karo prohibits a stone with an image of a lion in the synagogue,

22 See Divrei Yosef (siman 8) that rules this way based on the Shach Y.D 141:2

23 Shu”t Maharam Schick, Yoreh Deah 170

24 Shu”t Maharam Schick, Yoreh Deah 170

25 Darkei Teshuva (Yoreh Deah 141:35) cites Rav Yaakov Emden and Rav Yonatan Eibeshitz who strictly prohibited drawing images of people, even if beneficial (e.g., recognizing a deceased loved one). They extended this prohibition to photographs, including those of eminent Torah scholars, and advised people to avoid them altogether. This position gains support from the Ramban and Ritva, who considered even flat images to be forbidden.

26 See also Ben Ish Chai (Year II, Masei 9) and Rav Berachot (Maarechet Tzadi, page 130b), while acknowledging the permissibility according to halacha, advised against the practice of being photographed due to Kabbalistic reasons. He recommended people to be more stringent in this matter.

27 Yearot Devash, Vol.1 Derush 2

כי ידוע תדע כי אין לך פרצוף וצלם תבנית עץ ואבן שאין עליו שורה רוח ומזיק ומאד יש לאדם להזהר מבלי להיות בתוך ביתו פרצוף וצלם בצורה בולטת ואפי' צורה מצוירת בכותל יש להזהר כי אין לך צלם ודמות דלא שריה ביה רוח רעה

28 Shu”t Shevet Halevi vol. 7, Siman 137

29 See Sefer Ta’am Baruch (Lazerowski) pg. 11

By Rabbi Nissan Shalomayev

Rav, Bukharian Jewish Cong. of Hillcrest, Kehilat Ohr V’Achdut

What Makes a “Kosher” Tombstone ?

Typography

- Smaller Small Medium Big Bigger

- Default Helvetica Segoe Georgia Times

- Reading Mode