There are four passages where the Torah speaks of the great mitzvah of tefillin, one being at the end of Parshat Ekev, read a few weeks ago. In the list of 613, tefillin is actually two separate mitzvot—one for the head, and one for the arm. Some even say that tefillin counts as eight mitzvot, since we should multiply by four for the four times the Torah speaks of it! (Menachot 44a) Today, the mitzvah of tefillin is one of the best-known practices in all of Judaism, thanks in large part to the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s tefillin campaign starting in 1967, in the days leading up to the miraculous Six-Day War. We find many Jews who are otherwise secular or unaffiliated still laying tefillin every day. Following October 7, demand for tefillin was so high that there were reportedly shortages. Yet, tefillin binding hasn’t always been so widespread and well-known.

The Talmud (Berakhot 47a) suggests that one thing distinguishing Torah scholars (talmidei chakhamim) from the general public (am ha’aretz) is that the latter do not don tefillin. Even in responsa literature from the times of the Geonim (roughly 500-1000 CE), we find Jews asking if tefillin should be worn by all Jewish men, or if it was specifically reserved for great rabbis and Torah scholars. More puzzling still, we find that no other prophet besides Moses speaks of them, and there is no explicit mention of tefillin anywhere in the rest of Tanakh. Nor is there any historical or archaeological evidence of tefillin prior to about two millennia ago. Tefillin may just be the most mysterious Torah mitzvah we have. Where did it really come from, and what secrets does it contain?

The latter question is, surprisingly, easier to answer.

The Arizal (Rabbi Itzchak Luria, 1534-1572) taught that tefillin represents the light of the Mochin, the four supernal Sefirot of Keter, Chokhmah, Binah, and Da’at. Recall that Keter, literally the “crown”, is the source of willpower, the beginning of all human process. Then comes Chokhmah, often translated as “wisdom” but really referring to raw knowledge and information. Binah is “understanding”, building on the raw information, probing deeper, making connections, synthesizing. Finally, Da’at is applying the knowledge practically and living it. The Arizal taught that the head tefillin has four compartments and four parchments (of the four passages in the Torah describing tefillin) to parallel the four Sefirot of the Mochin (see Etz Chaim, Sha’ar HaKlalim, Ch. 12).

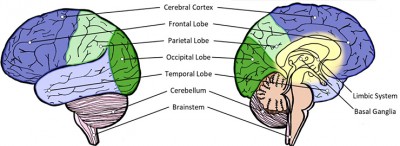

The Arizal was basing himself on the Zohar (III, 292b, Idra Zuta), which says much the same. Intriguingly, the Zohar seems to suggest that the four compartments parallel the four parts of the human brain. I believe this is referring to the left and right outer cortex, the inner part of the brain beneath the cortex, and the cerebellum at the back of the brain. The exact language of the Zohar is that there are three areas within the skull, which I think refers to the fact that the left and right brains are part of the same outer cortex. We’ve all heard much about the “left and right brain”, with the left brain described as being analytical, scientific, precise; while the right brain is described as artistic, creative, spiritual. (It is worth seeing neurologist Jill Bolte Taylor’s popular TED talk on this if you haven’t already.) These findings align well with the right pillar of the Sefirot being Chokhmah, Chessed, and Netzach, and the left pillar being Binah, Gevurah, and Hod. The right and left brains clearly mirror and manifest the higher-order arrangement of the Sefirot.

Meanwhile, the inner part of the brain, including what is often referred to as the “reptilian brain”, is known to be the most primeval and instinctive; the root of our base desires, needs, and wants. It neatly aligns with Keter. Finally, we have the cerebellum nicely paralleling Da’at, because the cerebellum is primarily involved with movement, coordination, and action, just as Da’at is about translating and applying our mental faculties into concrete actions. The cerebellum is heavily involved in maintaining balance, too, just as Da’at sits in the middle between Chokhmah and Binah to balance them.

Back to the Garden of Eden

The next page (293b) of the same Zohar has something even more profound and prescient. Here, the Zohar says that the four compartments of tefillin parallel the “four colours” in the eyes. There is no way the Zohar could have known this so many centuries ago, but today we know scientifically that our vision is generated by four types of microscopic photoreceptors: rods that distinguish between light and dark, and three types of cones that sense red, green, and blue wavelengths. (I won’t elaborate on this here, since it was already covered in-depth previously in ‘The Zohar’s Amazing Scientific Knowledge of the Eyes’.)

The Zohar has a lot more to say about tefillin, but I’ll add just one more incredible insight. The Zohar (I, 28b) connects the leather tefillin to the garments of leather that God made for Adam and Eve after the Forbidden Fruit (Genesis 3:21). Meaning, tefillin is so powerful it has the ability to rectify the very first sin. The Zohar here actually says that at the Sinai Revelation, Israel had the opportunity to rectify the entire cosmos and restore the Garden of Eden. But the sin with the Golden Calf brought it all tumbling down again, almost like a replay of the Forbidden Fruit incident. Henceforth, God commanded Israel the mitzvah of tefillin and tzitzit to fix the damage, with tefillin corresponding to the leather garments of Adam and Eve, and tzitzit corresponding to the fig leaf of Adam and Eve.

This leads to another famous idea that prior to the Torah revelation at Sinai, the Patriarchs and other holy people did still observe the Torah in their own way. They had other means to affect the same spiritual rectifications as we do through the mitzvot. For example, the episode where Jacob used various staves and planks to visually stimulate his sheep accomplished the same thing in the upper worlds as when we don tefillin today (see Zohar I, 162a). Similarly, our Sages taught that Abraham’s shoelaces and leather straps corresponded to tzitzit and tefillin (Sotah 17a). And so, like all mitzvot, tefillin is an eternal mitzvah that predates even Creation itself. It has manifested itself in different ways throughout history—from Adam’s leather garments, to Abraham’s shoe straps, to Jacob’s staves, and to the universal tefillin we all know and recognize today. The big question is how exactly did we get the tefillin we have today? When did they take on this final form? And why?

The Obscure Origins of Tefillin

As noted above, although the Torah of Moses itself mentions tefillin four times, they are never again mentioned in the rest of Tanakh. There is no explicit reference to anyone in Tanakh ever physically wearing tefillin! (Later, our Sages do find allusions to tefillin in the text—more on that below.) When the Torah was first translated into Greek some time in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE by seventy (or seventy-two) of our Sages, producing the Septuagint, the tefillin passages were interpreted metaphorically, suggesting that there is no need to physically bind objects onto our bodies, but rather that Torah should be “fixed” before our eyes and we should learn Torah all the time. Indeed, the tefillin passages were typically understood metaphorically by most Jewish groups in Second Temple times.

Philo of Alexandria (Yedidya haKohen, c. 20 BCE-50 CE), arguably the first Torah commentator and expositor of mitzvot, does not speak of physical objects to be bound on the arm or head. He also explains the Torah verses metaphorically, writing:

The law says it is proper to lay up justice in one’s heart, and to fasten it as a sign upon one’s head, and as frontlets before one’s eyes, figuratively intimating by the former expression that one ought to commit the precepts of justice, not to one’s ears, which are not trustworthy, for there is no credit due to the ears, but that most important and dominant part, stamping and impressing them on the most excellent of all offerings, a well-approved seal; and by the second expression, that it is necessary not only to form proper conceptions of what is right, but also to do what one has decided upon without delay. For the hand is the symbol of actions, to which Moses here commands the people to attach and fasten justice… (The Special Laws, IV, 137-138)

We know the Sadducees did not wear tefillin, and neither did their spiritual descendants, the Karaites. Samaritans also did not wear tefillin. They all argued that the mitzvah of tefillin in the Torah was never meant to be taken literally, since its first mention is “You shall have it as a sign on your arm, and a remembrance between your eyes, so that the Torah should be in your mouth…” (Exodus 13:9) The argument goes that, of course, we don’t literally put the Torah in our mouths, so why would we literally bind it to our arms or heads? Some of our own commentators suggest the same, including the Rashbam (Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir, c. 1085-1158) and the Ibn Ezra (Rabbi Avraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 1089-1167, although it should be pointed out that the latter has been censored, or even rewritten, in many modern publications!) This is further supported by archaeological evidence:

Despite Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira’s claim that he inherited his tefillin from his ancestors going back to the times of Ezekiel (Sanhedrin 92b), the earliest known tefillin we have today come from Qumran, from that same cache as the Dead Sea Scrolls. These are typically dated back to around the 1st century CE, and some possibly to the previous century. These tefillin are quite different than the ones we have today, with varying passages inside the boxes—most containing the Ten Commandments, and at least one with parashat Ha’azinu, the “Song of Moses”. Our Sages actually did debate whether the passage containing the Ten Commandments should be included in tefillin or not (see Sifrei Devarim 35), implying it was probably common practice two millennia ago, as we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Now, the Qumran community is typically identified with the Essenes, so it is quite possible that it was Essene Jews that first pioneered tefillin, which were then adopted by Pharisee Jews of the rabbinic tradition and eventually came into the final form we have today. We do have mention of tefillin in the late 1st century CE by Josephus in one short passage:

They are also to inscribe the principal blessings they have received from God upon their doors; and shew the same remembrance of them upon their arms: as also, they are to bear on their forehead, and their arm, those wonders which declare the power of God, and his good will towards them: that God’s readiness to bless them may appear every where conspicuous about them. (Antiquities, Book IV, 8:13)

It is worth noting that Josephus begins his autobiography by describing how he spent a great deal of time immersed in learning with all three main sects of Jews in his day—Sadducees, Pharisees, and Essenes—and ultimately chose to live as a Pharisee, which he felt was the true way.

There is a small source prior to Josephus that mentions tefillin, too, called the Letter of Aristeas. This is a letter written in Greek by one Aristeas to his brother Philocrates. It happens to be the earliest known source for the Septuagint story and how the Greek translation of the Torah was produced. (According to the Letter, there were seventy-two sages, not seventy, and their names are recorded!*) Both Josephus and Philo would later refer to this important historical text. In the Letter, we read that upon our garments he has given us a symbol of remembrance, and in like manner he has ordered us to put the divine oracles upon our gates and doors as a remembrance of God. And upon our hands, too, he expressly orders the symbol to be fastened, clearly showing that we ought to perform every act in righteousness, remembering (our own creation), and above all the fear of God.

It isn’t clear when exactly the letter was written, with most dating it to some time in the 2nd Century BCE. It’s quite incredible that it is a Greek text that first mentions the physical wearing of tefillin! It does not tell us what the tefillin look like, and seems to mention only the arm tefillin, not the head tefillin. By the time we get to Josephus one or two centuries later, we definitely have head tefillin, too. The only other early reference to tefillin from that time period is, ironically, the New Testament! In warning against the hypocrisy of certain Pharisees and corrupt rabbis, Jesus purportedly said:

The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat. So you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach. They tie up heavy, cumbersome loads and put them on other people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to lift a finger to move them. Everything they do is done for people to see: They make their phylacteries [ie. tefillin] wide and the tassels on their garments [ie. tzitzit] long; they love the place of honour at banquets and the most important seats in the synagogues; they love to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces and to be called “rabbi” by others. (Matthew 23:2-7)

We might be surprised to read that Jesus tells his disciples and his audience to do exactly as the Pharisees teach, meaning to follow all the halakhot of the Pharisees and rabbis punctiliously. He says this even more forcefully earlier in the same book:

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished. Therefore, anyone who sets aside one of the least of these commands and teaches others accordingly will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I tell you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven. (5:17-20)

Now, Jesus criticizes those rabbis that are hypocrites and pretend to be righteous and holy, showing off with large tefillin and long tzitzit. But in reality, they are corrupt in their hearts and full of sin, hungry for honour and riches, gloating when people call them “rabbi”. (Clearly, this problem is not just a modern-day one, and already existed two thousand years ago!) The term used here for tefillin is the Greek phylakteria, which literally means “amulet”. We do know that the wearing of protective amulets in ancient Greece was widespread, with many Greeks binding all kinds of amulets and parchments on their bodies with leather straps. That might explain why the earliest known historical mention of tefillin is a Greek text, written by a Jew with a Greek name (Aristeas) to a fellow Jew with a Greek name (Philocrates)!

In his Tangled Up in Text: Tefillin and the Ancient World, Dr. Yehudah Cohn suggests the possibility that even the term “tefillin” itself comes from a Greek word. We might assume it is based on the Hebrew tefillah, “prayer”, but tefillin are technically unrelated to prayer. Keep in mind that the mitzvah given in the Torah has nothing to do with prayer, and tefillin used to be worn all day, not just for prayer as we do today. Cohn suggests the possibility that tefillin comes from the Greek theo-philos or theo-philon, “love of God”. By wearing tefillin, one would demonstrate his love of God, since the mitzvah in the Torah twice connects tefillin to loving God, as we say regularly in the Shema. It therefore makes sense that the very pious and ascetic Essenes (whom our Sages called Hasidim, as I argued previously here) would be first to pioneer tefillin—and that would explain why the earliest known tefillin archaeologically come from their community. By the late first century, tefillin had become widespread among Pharisee leaders in the Holy Land, too, which would then explain why Josephus and the New Testament mention them, but Philo (being in Alexandria, Egypt) did not.

Surprises in the Talmud

In the centuries that followed, the Talmud was still pondering many tefillin fundamentals. One is the mysterious meaning of the Torah term totafot. Rabbi Akiva uses it to prove that tefillin must have four compartments, because tot means two in the Katfei language (possibly Coptic) and pat means two in the Afriki language, together making four (Sanhedrin 4b). It’s amazing that Rabbi Akiva links the etymology of a Torah word to foreign languages! And these are African languages, no less, which takes us right back to Egypt. (Recall that the tefillin passages in the Torah link the mitzvah directly to the Exodus out of Egypt.) In ancient Egypt, two of the main gods were called Toth, god of wisdom; and Ptah, the creator god who spoke the cosmos into existence. These names sound nearly identical to Rabbi Akiva’s etymology.

Egyptian gods Osiris (with the atef crown), Ptah, Isis (with a tefillin-looking box on her head), and Thoth

Indeed, we find Egyptian pharaohs and gods often depicted with various headdresses and arm wraps. One such depiction is of Osiris, a god of the afterlife, who wore the atef crown designating him king of the underworld. In his Mitzrayim, Midrash and Myth, Yisroel Cohen proposes that the word totafot may share a common origin with the word atef. More intriguing is the case of Osiris’ divine consort, Isis, goddess of life and “mother” of the pharaoh. Isis is typically drawn with a throne-shaped box on her head, beneath which is a strap going around. This is surprisingly similar to tefillin. And the Talmud appears to support the connection between tefillin and a female headdress:

In Shabbat 57b, the Talmud speaks of a totefet, a popular female headdress worn as a protective amulet. This sounds nearly identical to the totafot of tefillin! Of course, the Sages exempt women from laying tefillin (Kiddushin 33b-34a), although there are cases of women wearing tefillin, even in the Talmud itself (Eruvin 96a). Nonetheless, the Sages argued that since women are not obligated in learning Torah, they are also not obligated in wearing Torah, ie. laying tefillin, especially since the Torah juxtaposes learning with laying tefillin (as we recite in Shema). Although the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) ruled that a women may put on tzitzit or tefillin, without a berakhah, if she so wishes (Hilkhot Tzitzit 3:9), the accepted halakhah ultimately went stringent and essentially forbid women from laying tefillin. One reason for this was because wearing tefillin requires maintaining at all times a guf naki, a clean or pure body, which would be difficult during menstruation (lots more on this here). Still, there were minority views that questioned women’s exemption from tefillin, with the sharpest critique coming from one of the early Kabbalistic books, Sefer haKanah, which says:

The Holy One obligated her in the commandment of Torah study, which outweighs all other commandments combined, but the Sages exempted her because they encountered the word ‘sons’ in the text… As if that were not enough, they drew an analogy between tefillin and the study of Torah and exempted her from laying tefillin as well, and then they extrapolated from the case of tefillin to the whole category of time-bound commandments… And harshest of all, as if it were not enough for this lowly woman to be humiliated to the ground by being exempted from the most important of God’s commandments, is that they liken her to a slave, declaring that any commandment that is binding upon a woman is also binding upon a slave…

In any case, the Talmud linguistically connects the totafot of tefillin to the totefet of female protective amulets. This takes us back to the Greeks, among whom protective amulets (phylacteries) were commonly bound to the body. The Talmud affirms the protective powers of tefillin, with Reish Lakish saying that one who has tefillin upon him will have a long life, based on Isaiah 38:16 which says “Hashem is upon them, they will live, and altogether therein is the life of my spirit; and have me recover, and make me live.” The notion of Hashem being upon them is taken to refer to tefillin, where the word of God is literally upon a person.

If that’s the case, then one might argue: why shouldn’t women wear tefillin and reap the benefits? A totefet was a women’s headdress, after all, and the original “tefillin”—as per the Zohar—were the garments of leather God made for both Adam and Eve. Moreover, the Arizal described tefillin in feminine terms, too, teaching that the head tefillin is imbued with “Leah” energy while the arm tefillin is imbued with “Rachel” energy (see Sha’ar haPesukim on Iyov). Based on this, one might conversely argue that all of this feminine energy is the reason women don’t need tefillin. It is similar to the argument that women, of course, do not need the mitzvah of circumcision because they are already naturally and automatically born “circumcised”. Women have no need for these tikkunim, and come into this world starting on a higher plane. But there may be another explanation.

Based on the idea of tefillin as protective amulets—which both historical sources and the Talmud affirm—Dr. Yehudah Cohn (cited above) makes an excellent argument: Tefillin were meant to protect an individual on the go, when they were travelling away from home. Men wore tefillin all day when they were out and about. But women generally stayed home, and at home they were already protected by another amulet: the mezuzah! Our Sages spoke of the protective powers of the mezuzah in very similar fashion to tefillin. (That’s why today it has become quite common for people to check their mezuzot and tefillin when there is some serious health or wellbeing issue.) So, women didn’t need tefillin because they were already protected by the mezuzah of the house (bayit). The men who went out needed protection, too, so they carried a little “bayit” with them—and this would explain why the tefillin boxes are called batim, “houses”! And it might further explain one more mystery:

The Shelah (Rabbi Ishayah Halevi Horowitz, 1555-1630, on Ta’anit, Ner Mitzvah 30) explained that tefillin must be square to remind us of God’s House, the Beit haMikdash. In ancient times, and in medieval times, and reportedly even into the recent centuries in some parts of the world, there were people that made round tefillin. The Talmud (Megillah 24b) explicitly forbids this, and says square tefillin is halakhah l’Moshe miSinai—a law dating back to Moses himself. Tefillin must be square, ie. in the shape of a house.

The Talmud says a lot more about the tremendous power of tefillin. In one place, we read that a man who does not wear tefillin is “banned” from entering Heaven (Pesachim 113b), and in another that putting tefillin on a slave automatically emancipates him (Gitin 40a), and that even God Himself wears tefillin! (Berakhot 6a, a puzzle discussed at length in the recent series of classes on Names of God.) We learn that dreaming of putting on tefillin is a really great sign, too (Berakhot 57a). The reason? The Torah states that “all the peoples of the earth shall see that the name of Hashem is called upon you, and they shall be afraid of you” (Deuteronomy 28:10). As we saw previously, Hashem’s name being upon us refers to tefillin, and this causes the nations of the word to be in awe and trepidation of the Jews. We could certainly use a little more of this now, in light of the rampant, intense, and open antisemitism raging all over the world. The four passages of tefillin are all linked to the Exodus and the First Redemption, so perhaps it will be in the merit of tefillin that we will soon see the Final Redemption.

Shabbat Shalom!

Efraim Palvanov is a Canada-based life-long writer, researcher and educator who shares authentic Jewish wisdom intertwined with science, history, philosophy, and mysticism. Efraim has degrees in biology and education and currently serves as the head of the science department at Bnei Akiva Schools of Toronto. Visit mayimachronim.com for more thoughts like these and check out his YouTube channel @EfraimPalvanov.

* The names of the seventy-two sages that produced the Septuagint, as given in the Letter of Aristeas: “Of the first tribe, Joseph, Ezekiah, Zachariah, John, Ezekiah, Elisha. Of the second tribe, Judas, Simon, Samuel, Adaeus, Mattathias, Eschlemias. Of the third tribe, Nehemiah, Joseph, Theodosius, Baseas, Ornias, Dakis. Of the fourth tribe, Jonathan, Abraeus, Elisha, Ananias, Chabrias…. Of the fifth tribe, Isaac, Jacob, Jesus, Sabbataeus, Simon, Levi. Of the sixth tribe, Judas, Joseph, Simon, Zacharias, Samuel, Selemias. Of the seventh tribe, Sabbataeus, Zedekiah, Jacob, Isaac, Jesias, Natthaeus. Of the eighth tribe Theodosius, Jason, Jesus, Theodotus, John, Jonathan. Of the ninth tribe, Theophilus, Abraham, Arsamos, Jason, Endemias, Daniel. Of the tenth tribe, Jeremiah, Eleazar, Zachariah, Baneas, Elisha, Dathaeus. Of the eleventh tribe, Samuel, Joseph, Judas, Jonathes, Chabu, Dositheus. Of the twelfth tribe, Isaelus, John, Theodosius, Arsamos, Abietes, Ezekiel. They were seventy-two in all.”

Mysteries & Secrets Of Tefillin

Typography

- Smaller Small Medium Big Bigger

- Default Helvetica Segoe Georgia Times

- Reading Mode