Parashat Kedoshim contains two prohibitions on curses.

“Do not curse the deaf,” (chapter 19, verse 14) means, a person who does not hear curses, therefore does not fret about any offenses inflicted upon him. More generally, this means to not mock or take advantage of those who cannot defend themselves.

The Torah warns, "Whoever curses his father or his mother must be put to death." (Chapter 20, verse 9)

“Do not curse the judge and do not curse the leader of your People," (Shemot, Mishpatim 22:27). By “leader,” the parashah refers to a king who behaves with dignity, as befits the head of the Jewish People.

So, the Torah forbids cursing and at the same time specifies who may not be cursed.

Is it okay to curse someone who is not a deaf person, judge, leader of the People, or a parent?

The Torah cites different types of people as examples: from the most insignificant—the deaf—to the most outstanding— a “leader,” in order to tell us: do not curse anyone—including yourself!

“You shall not go around as a rachil, talebearer, among your People; do not stand by the blood of your brother,” (Shemot 19:16).

Why are the two prohibitions combined?

In Soviet Russia my neighbor was detained for a deed punishable nowhere else except in the USSR. Hoping to help, his friends spoke to the investigator, a neighbor of theirs with whom they were acquainted. The investigator promised, “I will immediately talk to whomever is necessary, and your friend will be released.” Then, along came a chatterbox who informed the investigator that the other evening the person arrested snitched on the investigator as a negligent worker. The investigator was incensed! “I will not trouble myself for this lowlife! Let him rot in prison!” The man was soon convicted and served a full sentence.

Do not stand by the blood of your brother means that if someone is in trouble, one must do everything possible to secure their safety—you cannot stand aside. But, if you violated the prohibition, “do not go around as a talebearer among your People.” If you harm someone with evil talk, it may happen that this very person will refuse to help in your time of need.

The Talmud (Tractate Avoda Zara 19b) expounds, “Rav Alexandri once exclaimed: ‘Who wants long life?’ People came to him for the secret of longevity. He opened T'hillim and read Psalm 34: ‘Who is the man who desires life, who loves days to see goodness? Guard your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceitfully.’”

Now, what is rechilus (“talebearing”) and who is called a rachil?

A rachil is one who tells another person what someone has gossipped about them. Even if only repeating facts that are generally known, the repetition might come to harm the original person as well as the one originally spoken about. Even if the “tale” is true, the one who repeats it commits an evil. So great is the evil that it could even lead to the destruction of the foundations of the world! Only in a case where one is legitimately warning of harm is it permissible to tell someone a potentially hurtful truth. For example, a friend partners with someone you can know to have previously swindled someone else. What should you do? Certain complicated conditions must be met in order to bypass the prohibition of rechilut, a halachic authority should be consulted.

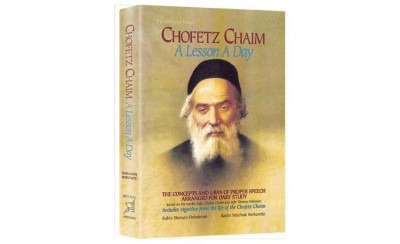

Rav Yisrael Meir Kagan, the Chofetz Chaim (defined as one desiring life), authored a self-titled work on how to be careful with the spoken and written word. Its three main principles are not to gossip, listen to gossip, or rely on gossip if you have already heard it. Rav Kagan, whose name is derived from Psalms 34, published his masterpiece anonymously, astonishing the Jewish world, “A great man has appeared among us!”

Among the Jews, personal behavior decides everything, and not the appeals that a person utters. Among the Jewish People, what counts is how one conducts oneself, not what he preaches. Hence, learned rabbis would often visit the Chofetz Chaim to “spy” on him. They would converse on various topics to see if they could coerce the sage to speak lashon hara, an action that never transpired! So, the “spies” announced Rabbi Yisrael Meir was conducting himself in complete accordance with his written word. In harmony with his name, Kagan is the Russian for “Kohain,” the Chofetz Chaim became the spiritual leader of Eastern European Jews and one of the greatest authorities in modern Judaism. As is the custom among our great Torah sages, Rabbi Kagan became known after the title of his most famous work—Chofetz Chaim.

Copyright© 2023 by The LaMaalot Foundation. Talks on the Torah, by Rabbi Yitzchak Zilber is catalogued at The Library of Congress. All rights reserved. Printed in China by Best Win Printing, Shenzhen, China.

How The Chofetz Chaim Came To Be

Typography

- Smaller Small Medium Big Bigger

- Default Helvetica Segoe Georgia Times

- Reading Mode